A systematic review examining twenty-one randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 3,176 patients concluded that acupuncture provides both clinically significant pain relief and measurable biological protection in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis (KOA) [1]. Researchers reported that patients receiving acupuncture consistently experienced reductions of two to four points on the Visual Analogue Scale and functional improvements of 25 to 40 percent on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index compared with sham procedures or usual care [1].

In one of the largest RCTs included, Berman and colleagues followed 570 participants who received twenty-three acupuncture sessions over twenty-six weeks and noted marked improvements in WOMAC scores, walking distance, and quality of life [1]. Tu and colleagues similarly demonstrated a 60.3 percent response rate with electroacupuncture and manual acupuncture after twenty-four sessions, an outcome that far exceeded that of sham controls [1].

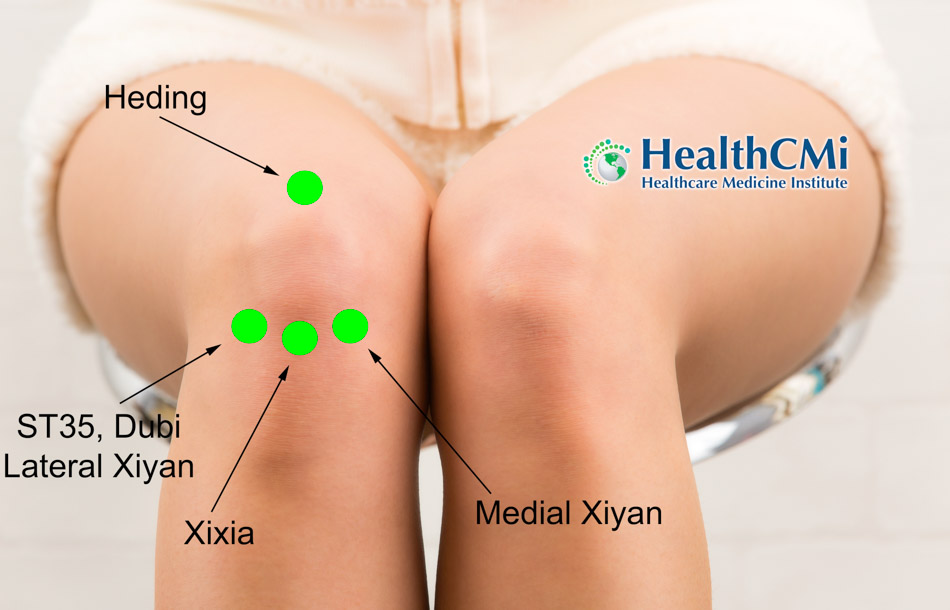

The acupuncture prescriptions used across these trials were consistent and centered on a set of local and distal points chosen for their musculoskeletal indications. Dubi (ST35), Xuehai (SP10), Yanglingquan (GB34), Yinlingquan (SP9), Zusanli (ST36), and Weizhong (BL40) were frequently applied around the knee joint, often supplemented by Xiyan (EX-LE5), Heding (EX-LE2), and Neixiyan (EX-LE4). Tender Ashi points were added when palpation revealed local reactivity. Distal points such as Hegu (LI4), Taichong (LV3), and Sanyinjiao (SP6) were employed to regulate qi and blood, while KI3 (Taixi) was selected to tonify the Kidney and benefit the knees [1].

The procedures were carried out with standardized methods. Manual acupuncture typically used stainless steel needles with diameters of 0.25 to 0.30 mm inserted perpendicularly or obliquely to depths of 10 to 30 mm depending on the acupoint. Needles were retained for 20 to 30 minutes per session, administered two to three times weekly over four to six weeks [1]. Electroacupuncture employed the same gauge needles with electrical stimulation set to low frequency (2–4 Hz) for chronic pain or high frequency (80–120 Hz) for acute exacerbations, applied for 20 to 40 minutes per session at a rate of two to three treatments weekly for four to eight weeks [1]. Warm needle acupuncture added moxa to the shaft of the needle, producing a thermogenic effect particularly suited to cold-damp presentations. Sessions lasted 30 to 40 minutes, delivered two to three times weekly for six to eight weeks [1]. In cases of fibrotic restriction or adhesions, the small needle knife technique was used for short sessions of 10 to 20 minutes, often requiring only one to three treatments to restore mobility, and clinical data showed significant improvements in Oxford Knee Scores and gait analysis [1].

Combination therapies enhanced outcomes further. Trials that combined electroacupuncture with moxibustion or acupuncture with sodium hyaluronate injection demonstrated superior analgesic and functional results compared with standard pharmacological care. Biochemical markers also shifted with these integrated interventions. For example, levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) decreased, while serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and bone gamma-carboxyglutamic acid-containing protein increased, supporting cartilage and bone metabolism [1].

Mechanistic studies clarify how these interventions influence the degenerative process of KOA. Acupuncture was shown to suppress pro-inflammatory signaling cascades, particularly NF-κB and TLR4/MyD88 pathways, thereby reducing serum IL-1β, TNF-α, and MMP-13 while simultaneously upregulating IL-4 and IL-10 [1]. Fire needle therapy promoted a macrophage shift from the destructive M1 phenotype toward the reparative M2 state, downregulating CD86 and upregulating CD206 [1]. Warm needle acupuncture enhanced antioxidant defenses, increasing expression of superoxide dismutase-2 and reducing NOX2-positive cells, thereby limiting oxidative damage to chondrocytes [1]. Electroacupuncture was also found to reduce Bax and caspase-3 expression while enhancing Bcl-2, protecting cartilage through inhibition of apoptosis, and to upregulate GPX4 and collagen type II expression, thereby suppressing ferroptosis and preserving structural integrity [1].

At the level of cell survival and repair, acupuncture promoted balanced autophagy. By activating the Pink1-Parkin pathway it supported mitochondrial autophagy, while regulation of the AMPK/mTOR pathway prevented excessive autophagic cell death. Electroacupuncture further increased protective microRNAs such as miR-146a and miR-140-5p, delaying chondrocyte senescence [1]. Neuroregulatory effects were also documented: plasma beta-endorphin increased after electroacupuncture, cortisol decreased, and the MCP-1/CCR2 axis responsible for nociceptive sensitization was inhibited [1]. Functional MRI demonstrated improved connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex, regions associated with descending pain modulation, following acupuncture treatment [1].

For acupuncturists in clinical practice, the implications are clear. Treatment frequencies of two to three times weekly, session durations of 20 to 40 minutes, and needle diameters in the 0.25 to 0.30 mm range were consistently used in successful protocols. Electroacupuncture at low frequency and high intensity applied to ST36 and GB34 has demonstrated particular efficacy in chronic KOA [1]. Warm needle acupuncture provides a reliable strategy in patients with cold-damp symptom patterns [1].

The review therefore establishes that acupuncture is not only a symptomatic therapy but a disease-modifying approach for KOA. Patients experienced measurable improvements in pain and mobility, and laboratory analyses confirmed reductions in pro-inflammatory mediators, oxidative stress, and apoptosis markers. Neuroimaging studies further validated changes in brain networks associated with pain perception and regulation. Collectively, these findings position acupuncture as a rigorously tested intervention that alleviates symptoms and protects joint structure, offering practitioners reproducible clinical protocols supported by modern biomedical validation [1].

Source:

[1] Kaifang Yao, Md Forhad Shamim, Jiaqi Xia, Tingting Liu, Yi Guo, and Xiaowei Lin. “Therapeutic Potential of Acupuncture in Knee Osteoarthritis: Clinical Efficacy and Mechanistic Insights.” Journal of Inflammation Research (2025): 12169–12190.